Stranded in Panama: The Human Cost of US Deportation Policies

The detention of nearly 300 deportees, including 30 Indians, in a Panama City hotel has brought to light the complex interplay of international migration policies, diplomatic hurdles, and human rights concerns. This development, a direct outcome of the US deportation process, raises crucial questions about the accountability of both the sending and receiving nations, as well as the fate of these individuals caught in legal limbo.

At the heart of the matter is the global crackdown on illegal immigration, which the United States has intensified over the past years. While Washington justifies its deportation measures as necessary to maintain national security and curb undocumented migration, it effectively shifts the burden onto transit nations like Panama. These deportees, originating from India, Iran, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China, are unable to return directly to their home countries due to bureaucratic verification processes, diplomatic bottlenecks, and in some cases, concerns about their safety upon repatriation.

India’s stance on illegal migration has been firm, as reiterated by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal, who emphasized the need for verification of nationality before accepting deported individuals. This cautious approach is understandable given the risks of human trafficking, identity fraud, and broader security concerns. However, the situation in Panama raises an important question: Should origin countries take responsibility for their citizens regardless of the circumstances, or do the nuances of each case demand a more meticulous assessment?

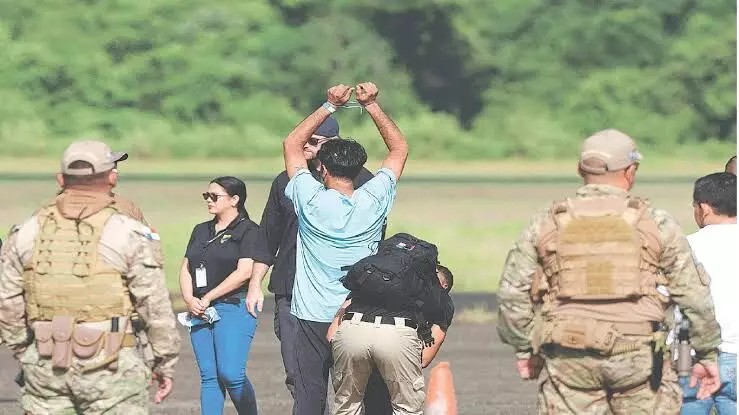

While Panama has agreed to temporarily house these individuals, the arrangement appears more like an involuntary detention rather than a humanitarian response. Reports indicate that the migrants, including women and children, are confined to their rooms in the Decapolis Hotel in Panama City under guard supervision. Though they are provided with food and medical care, their inability to leave the premises effectively turns the hotel into a de facto detention center. This brings into question whether such measures violate international human rights laws, which stipulate that migrants should not be held indefinitely without due process.

Senior foreign affairs analysts argue that this crisis is emblematic of a larger trend: the externalization of migration control by the US and other Western nations. By deporting migrants without securing a structured repatriation plan, the US effectively offloads its immigration issues onto third countries, many of which lack the resources to handle such situations effectively. This tactic mirrors the controversial agreements that European nations have signed with countries like Libya and Turkey to prevent asylum seekers from reaching their shores.

The fundamental flaw in this approach is that it prioritizes political optics over sustainable solutions.

The case of the detained Indians further complicates India’s diplomatic obligations. Historically, India has taken a strong stance against illegal migration, but at the same time, it cannot completely disengage from the plight of its nationals stranded in foreign lands. While verification of nationality is a necessary procedure, excessive delays in this process only exacerbate the humanitarian crisis. Furthermore, India must also consider the geopolitical implications of allowing its citizens to be held under conditions that may violate human rights.

The broader question remains: who is responsible for these migrants? While the US initiated their deportation, it cannot absolve itself of responsibility once the individuals have left its borders. Transit countries like Panama are unwilling hosts, caught between diplomatic pressures and limited resources. Meanwhile, origin countries like India must strike a balance between enforcing legal migration policies and safeguarding the dignity of their citizens.

A long-term solution to such crises requires greater international cooperation. The current model—where powerful nations deport migrants without coordination with the relevant stakeholders—creates diplomatic deadlocks and humanitarian crises. The United Nations and international migration bodies must step in to establish a more structured framework for deportations, ensuring that they are conducted in a manner that respects human rights and does not shift the burden unfairly onto third countries.

As it stands, the migrants detained in Panama represent a failure of global migration governance. Unless origin countries, transit nations, and the US work together to find a sustainable resolution, such incidents will only continue to unfold, highlighting the moral and ethical failures of an international system that treats migrants as mere logistical challenges rather than human beings with rights and dignity.